Chapter 4 Inference on β in Simple Linear Regression

4.1 Inference Goals

A fundamental task in statistics is inference, in which we use a sample of data to make generalizations about relationships in larger populations. Inference is a key component of an association analysis (see Section 1.2.1). Inference is usually conducted via hypothesis tests and confidence intervals.

Statistical inference is typically driven by an underlying scientific goal. A standard inferential question for a regression analysis is something like: Is there a relationship between ‘x’ and the average value of ‘y’?, where ‘x’ and ‘y’ are a predictor and outcome of interest. To answer this question using regression, we first need to translate it into a statistical question about specific model parameters.

It helps to first note that if there is no relationship between the variable x and the average outcome E[Y], then an appropriate linear model is the intercept-only model:

Yi=β0+ϵi. In equation (4.1), the predictor x does not appear at all, and so the regression line is simply a horizontal line with intercept β0. Figure 4.1 shows an example of data generated from a model in which there is no relationship between Yi and xi.

Figure 4.1: Example data from a hypothetical regression model with β0=3 and β1=0. The black line shows the true mean of y as a function of x.

How is the intercept-only model useful? Well, it allows to change the scientific question:

Is there a relationship between ‘x’ and the average value of ‘y’?

into a statistical question:

In the model Yi=β0+β1xi+ϵi, is β1≠0?

If the answer to this question is “No”, then β1=0 and we are left with the intercept-only model. Testing against a null hypothesis of zero is by far the most common test done in regression models, since this allows us to test for an association.

Remember that in Section 3.2 we pointed out that the slope estimate ˆβ1 had the same sign as the correlation between x and y? Well, if that correlation is zero, then the estimated line would be flat–just like it is when there is no relationship between x and y.

Example 4.1 In the penguin data we might ask: Is there a relationship between flipper length and body mass in penguins? The corresponding statistical question is: In the SLR model with xi= flipper length and Yi= body mass, is β1≠0? We saw in Example 3.1 that the estimated SLR equation for the penguin data was E[Yi]=−5780.83+49.69xi. Thus, the estimated slope is 49.7 g/mm. Clearly this value is not 0. But is it meaningfully different from 0? We address that question in the remainder of this chapter.

4.2 Standard Error of β1

Before getting into the detail of how we conduct hypothesis tests for regression parameters, we first need to review a few key statistical concepts. The first is standard error.

4.2.1 Sampling Distribution of ˆβ1

The notation ˆβ1 actually refers to two different quantities. On one hand, this is the estimated slope of the linear regression line; that is, ˆβ1 is a number or an estimate. But ˆβ1=Sxy/Sxx also denotes an estimator, which is a rule for calculating an estimate from a dataset.

As an estimator, ˆβ1 has a distribution. We have previously seen that under the standard SLR assumptions:

- E[ˆβ1]=β1

- Var[ˆβ1]=σ2/Sxx

The value of Var[ˆβ1] tells about how much variation there is the values of ˆβ1 calculated from many different datasets. If we conduct repeated experiments all using the same population and settings, we obtain a different ˆβ1 each time.

- The distribution of values we obtain is called the of ˆβ1

- The standard deviation (or the variance) of this distribution tells us about the uncertainty in ˆβ1

4.2.2 Standard Errors

The standard deviation of the sampling distribution of ˆβ1 is called the standard error of ˆβ1 and it is denoted:

se(ˆβ1)=√Var(ˆβ1)=√σ2/Sxx The value of se(ˆβ1) depends on three factors:

- The variance of the error terms (σ2)

- The variation in the values of xi (via Sxx)

- The number of observations (via Sxx)

It’s important to note that we don’t know σ2, but we can estimate it as ˆσ2 (see Section 3.5.3). This gives an estimate of Var(ˆβ1): ^Var(ˆβ1)=ˆσ2Sxx=1Sxx1n−2n∑i=1e2i So we calculate the estimated standard error as ^se(ˆβ1)=√MSresSxx

4.3 Not Regression: One-sample t-test

To see how we incorporate se(ˆβ1) into a hypothesis test, let’s first go back to perhaps the most well-known test in statistics, the one-sample t-test.

For a one-sample t-test, we assume that we have an independent sample of values y1, y2, …, yn from a population in which Yi∼N(μ,σ2). Our hypothesis is then to test whether μ≠μ0 for some chosen value of μ0. We can write this as: H0:μ=μ0vs.HA:μ≠μ0 We use the test statistic t=ˆμ−μ0se(ˆμ). If H0 is true, then t follows a T-distribution with n−1 degrees of freedom, i.e. t∼T(n−1).

- If t is “large”, then we reject H0 in favor of HA

- If t is not “large”, then we do not reject H0

But what does “large” value of t mean? Large t means ¯y is far from the hypothesized value μ0. To account for the variability in the distribution of ˆβ1, we divide ¯y−μ0 by its standard error. This is because a large difference between ¯y and μ0 is more meaningful when ¯y has smaller variance.

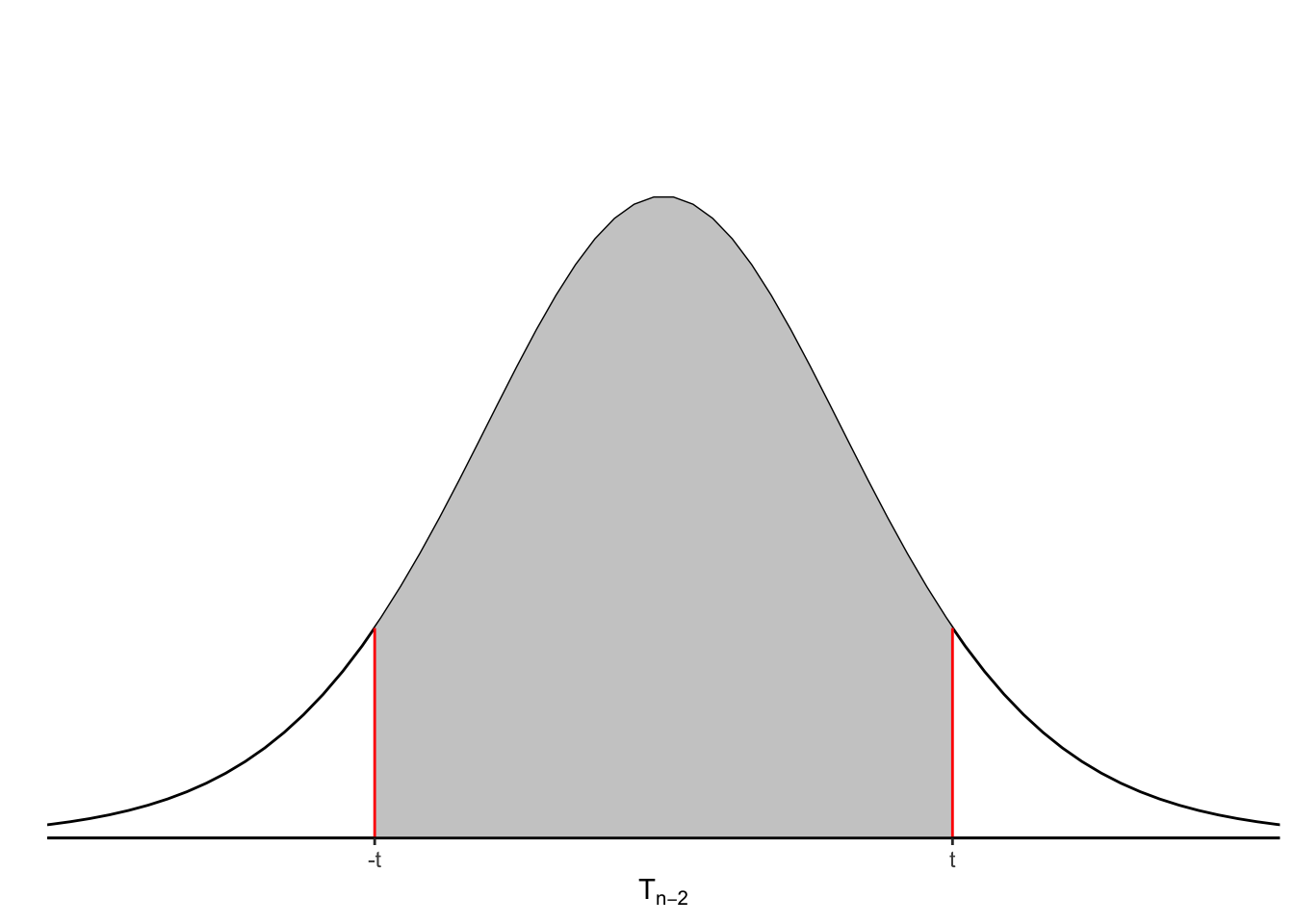

We then compare t to the Tn−1 distribution and compute P(T>|t|):

Figure 4.2: Density curve for T-distribution. Shaded areas on left and right represent P(T>|t|).

This probability is given by the shaded areas on the right and left in Figure 4.2. Since our alternative hypothesis is two-sided (as opposed to a one-sided hypothesis such as H0:μ>μ0), then we need to consider the values in both directions.

If p=P(T>|t|) (the “p-value”) is smaller than the chosen critical value α, then we reject H0. How to choose α is the subject of much debate, but a widely used value is 0.05. In some contexts, 0.01 and 0.1 are also used as critical values for rejecting H0.

If P(T>|t|)>α, then we fail to reject H0. It’s important to note that failing to reject H0 is not the same as proving H0!

Why is t∼Tn−1 and not t∼N(0,1)? This is because we have estimated the standard error ^se(¯y)=s/√n, and so t has more variation than a normal distribution. Part of what makes tests of this form so useful is that when n (the sample size) is large enough, then t has a T-distribution, even if Y does not have a normal distribution! This is a consequence of the Central Limit Theorem (CLT).

The CLT tells us that for a sequence of random variables X1, X2, with finite mean μ and finite variance σ2, the distribution of the mean of the observations ¯Xn=1n∑ni=1Xi can be approximated by a normal distribution with mean μ and variance σ2/n when n is sufficiently large.

4.4 p-values

While widely used, p-values are commonly mis-used. It’s important to keep in mind what a p-value can (and can’t!) tell you. A formal definition for a p-value is:

Definition 4.1 The p-value for a hypothesis test is the probability, if H0 is true, of observing a test statistic the same or more in favor of the alternative hypothesis than the result that was obtained.

The underlying idea is that a small p-value means that getting data like what we observed is not very compatible with H0 being true.

Incorrect interpretations of p-values:

- Probability the null hypothesis is incorrect

- Probability that the alternative hypothesis is true

- Probability of these results occurring by chance

In 2018, the American Statistical Association (ASA) published a statement about p-values.5 Included in that statement were the following reminders:

- p-values can indicate how incompatible the data are with a specified statistical model.

- p-values do not measure the probability that the studied hypothesis is true, or the probability that the data were produced by random chance alone.

- Scientific conclusions and business or policy decisions should not be based only on whether a p-value passes a specific threshold.

- Proper inference requires full reporting and transparency.

- A p-value, or statistical significance, does not measure the size of an effect or the importance of a result.

- By itself, a p-value does not provide a good measure of evidence regarding a model or hypothesis.

4.5 Hypothesis Testing for β1

In simple linear regression, we can conduct a hypothesis test for β1 just like how we conducted the one-sample t-test.

First, we set up the null and alternative hypotheses:

H0:β1=β10 HA:β1≠β106

Most commonly, β10=0, which mean we are testing whether there is a relationship between x and E[Y]. The t statistic is:

t=ˆβ1−β10^se(ˆβ1)=ˆβ1−β10√ˆσ2/Sxx=ˆβ1−β10√1Sxx1n−2∑ni=1e2i

If ϵi∼N(0,σ2) and H0 is true, then t has a T-distribution with n−2 degrees of freedom. If H0 is true, but ϵi is not normally distributed, then t follows a Tn−2 distribution approximately, because of the CLT. We reject H0 at the α level if P(T>|t|)<α.

Example 4.2 Let’s return to the penguin data in Example 4.1, in which we asked: In the SLR model with xi= flipper length and Yi= body mass, is β1≠0?

We previously calculated the estimated slope as ˆβ1=49.7. From the question formulation, we know that the test value β10=0. To calculate t, we now need to compute ^se(ˆβ1)=ˆσ2/Sxx.

We can obtain ˆσ2 from R, either from the output of summary() or by calculating it directly:

penguin_lm <- lm(body_mass_g ~ flipper_length_mm, data=penguins)

sig2hat <- summary(penguin_lm)$sigma^2

sig2hat## [1] 155455.3## [1] 155455.3We can then calculate Sxx as:

sxx <- sum(penguins$flipper_length_mm^2, na.rm=T) - 1/nobs(penguin_lm)*sum(penguins$flipper_length_mm, na.rm=T)^2

sxx## [1] 67426.54Now we combine these values to compute

t=ˆβ1−β10√ˆσ2/Sxx=49.7−0√155455.3/67426.54=32.7 In R, this computation is:

## flipper_length_mm

## 32.72223We can then compute the p-value, by comparing to a T-distribution:

## flipper_length_mm

## 4.370681e-107This tell us that P(T>|32.7|)<0.0001. And so we reject H0 at the α=0.001 level.

Although the method just describe works, it can be tedious and is prone to mistakes. Since the null hypothesis H0:β1=0 is so commonly tested, R provides the results of the corresponding hypothesis test in its standard output.

Example 4.3 Compare the following output with the results calculated manually in Example 4.2.

## # A tibble: 2 × 5

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) -5781. 306. -18.9 5.59e- 55

## 2 flipper_length_mm 49.7 1.52 32.7 4.37e-107We see a column with ˆβ1, ^se(ˆβ1), t, and p! This same information is also available from the summmary() command:

##

## Call:

## lm(formula = body_mass_g ~ flipper_length_mm, data = penguins)

##

## Residuals:

## Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

## -1058.80 -259.27 -26.88 247.33 1288.69

##

## Coefficients:

## Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

## (Intercept) -5780.831 305.815 -18.90 <2e-16 ***

## flipper_length_mm 49.686 1.518 32.72 <2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error: 394.3 on 340 degrees of freedom

## (2 observations deleted due to missingness)

## Multiple R-squared: 0.759, Adjusted R-squared: 0.7583

## F-statistic: 1071 on 1 and 340 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-164.6 Other forms of hypothesis tests for β1

4.6.1 Testing against values other than 0

Although less common, it is possible to conduct hypothesis tests against a null value other than zero. For example, we could set up the hypotheses

H0:β1=40vs.HA:β1≠40

To conduct this hypothesis test, we would need to use the “by hand” procedure for computing t and p.

Example 4.4 In the penguin data from Example 4.1, what is the conclusion of testing the null hypothesis in Equation (4.2)?

We compute t as:

t=49.7−401.52=6.38

In R, this can be computed as:

## [1] 6.378781We can then compute the p-value, by comparing to a T-distribution:

## [1] 5.832893e-10We reject the null hypothesis that β1=40 at the α<0.0001 level.

4.6.2 One-sided tests

Another alternative is a one-sided test, which involves null and alternative hypotheses of the form:

H0:β1≥0vs.HA:β1<0

With one-sided hypotheses, the calculation of t is the same as in the two-sided setting, but the calculation of the p-value is different. Instead of p=P(T>|t|), we evaluate p=P(T>t) or P(T<p), depending on whether the alternative hypothesis is greater than (>) or less than (<). The direction of the inequality for calculating the p-value should always match the direction in the alternative hypothesis.

Example 4.5 In the penguin data from Example 4.1, what is the conclusion from a test of the hypotheses in equation (4.2)?

We can use the value t=32.7 calculated earlier. But now we evaluated the p-value as:

## [1] 1In this example, p≈1, so we fail to reject the null hypothesis that β1 is greater than or equal to zero. This should come as no surprise, since our estimate ˆβ1 is (much) greater than zero.

4.7 Confidence Intervals (CIs)

4.7.1 Definition and Interpretation

Hypothesis tests provide an answer to a specific question (Is there evidence to reject the null hypothesis?), but they don’t directly provide information about the uncertainty in the point estimates. In many contexts, what is often more useful than a conclusion from a hypothesis test is an estimate of a parameter and its uncertainty. Confidence intervals provide a way to describe the uncertainty in a parameter estimate.

Definition 4.2 A (1−α)100% confidence interval is a random interval that, if the model is correct, would include (“cover”) the true value of the parameter with probability (1−α).

In this definition, it is important to note that the interval is random, not the parameter. The parameter is a fixed, but unknown, constant, and so it cannot have a probability distribution associated with it.7 A common incorrect interpretation of a CI is that the probability of the parameter being in the interval is (1−α)100%.

For a single dataset, there is no guarantee that the true value of a parameter will be included within the confidence interval. But if the model is correct, then an interval generated by the same procedure should include the true value in (1−α)100% of analysis of independently-collected data. Figure 4.3 shows the coverage of 95% CIs calculated for 100 simulated datasets when the true value of β1=2.

Figure 4.3: Example of coverage of 95% CIs in 100 simulated datasets.

4.7.2 Inverting a Hypothesis Test

To create a confidence interval, we invert a hypothesis test. Recall that for testing the null hypothesis H0:β1=β10 against the alternative hypothesis HA:β1≠β10, we computed the test statistic t=ˆβ1−β10^se(ˆβ1) by plugging in ˆβ1, ^se(ˆβ1), and β10. We then compared the value of t to a Tn−2 distribution to compute the p-value p=P(T>|t|). For a confidence interval, we reverse this process. That is, we plug in ˆβ1, ^se(ˆβ1), and t, then solve for β10 as an unknown value.

The distribution of t=ˆβ1−β1^se(ˆβ1) is Tn−2. This distribution has mean zero and a standardized variance (it’s close to 1, although not exactly 1). There exists a number, which we denote tα/2, such that the area under the curve between −tα/2 and tα/2 is 1−α. Mathematically, this can be written:

P(−tα/2≤ˆβ1−β1^se(ˆβ1)≤tα/2)=1−α

Graphically, this looks like:

We can rearrange equation (4.3), so that β1 is alone in the middle:

1−α=P(−tα/2^se(ˆβ1)≤ˆβ1−β1≤tα/2^se(ˆβ1))=P(tα/2^se(ˆβ1)≥β1−ˆβ1≥−tα/2^se(ˆβ1))=P(ˆβ1+tα/2^se(ˆβ1)≥β1≥ˆβ1−tα/2^se(ˆβ1))=P(ˆβ1−tα/2^se(ˆβ1)≤β1≤ˆβ1+tα/2^se(ˆβ1))

4.8 CIs for β1

The procedure from the previous section gives a (1−α)100% confidence interval for β1: (ˆβ1−tα/2^se(ˆβ1),ˆβ1+tα/2^se(ˆβ1))

4.8.1 Confidence Intervals “by hand” in R

To compute a confidence interval “by hand” in R, we can plug in the appropriate values into the formulas. The estimates ˆβ1 and ^se(ˆβ1) can be calculated from an lm object.

To compute tα/2, use the qt() command, which can be used to find x such that P(T<x)=˜p for a given value of ˜p.

In order to compute tα/2, we need to find x such that P(T<x)=1−α/2.

Because of the symmetry of the T distribution, this will yield an x=tα/2.

This can be implemented in the following code:

## [1] 1.984467An alternative approach is to find P(T>x)=α/2. To do this using qt(), set the lower=FALSE option:

## [1] 1.984467Example 4.6 In the penguin data, suppose we wish to construct a confidence interval for β1 using the formulas. This can be done with the following code:

penguin_lm <- lm(body_mass_g~flipper_length_mm,

data=penguins)

alpha <- 0.05

t_alphaOver2 <- qt(1-alpha/2,

df = nobs(penguin_lm)-2)

CI95Lower <- coef(penguin_lm)[2] - t_alphaOver2 * tidy(penguin_lm)$std.error[2]

CI95Upper <- coef(penguin_lm)[2] + t_alphaOver2 * tidy(penguin_lm)$std.error[2]

c(CI95Lower, CI95Upper)## flipper_length_mm flipper_length_mm

## 46.69892 52.672214.8.2 Confidence Intervals in R

In practice, it is much simpler to let R compute the confidence interval for you. Two standard options for this are:

- Add

conf.int=TRUEwhen callingtidy()on thelmoutput. This will add aconf.lowandconf.highcolumn to the tidy output. By default, a 95% confidence interval is constructed. To change the level, setconf.level=to a different value. - Call the

confint()command directly on thelmobject. This prints the confidence intervals only (no point estimates). To change the level, set thelevel=argument.

## # A tibble: 2 × 7

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) -5781. 306. -18.9 5.59e- 55 -6382. -5179.

## 2 flipper_length_mm 49.7 1.52 32.7 4.37e-107 46.7 52.7## # A tibble: 2 × 7

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) -5781. 306. -18.9 5.59e- 55 -6573. -4989.

## 2 flipper_length_mm 49.7 1.52 32.7 4.37e-107 45.8 53.6## 2.5 % 97.5 %

## (Intercept) -6382.35801 -5179.30471

## flipper_length_mm 46.69892 52.672214.9 Summarizing Inference for β1

When testing H0:β1=0 vs. HA:β1≠0, it is best to write a complete sentence explaining your conclusion. In the sentence, clear describe the null hypothesis and whether it was rejected or not. Report the exact p-value, unless it is below 0.0001, in which case writing p<0.0001 is sufficient.

Confidence intervals are generally reported in parentheses after a point estimate is given. It is standard to specify the confidence level when doing so.

Example 4.7 We can update the interpretation summary from Example 2.8 by adding a second sentence so that our full conclusion is:

A difference of one mm in flipper length is associated with an estimated difference of 49.7 g (95% CI: 46.7, 52.7) greater average body mass among penguins in Antarctica. We reject the null hypothesis that there is no linear relationship between flipper length and average penguin body mass (p<0.0001).

Note that we have used the phrase “no linear relationship” when describing the null hypothesis that has been rejected. The SLR model can only tell us about a linear relationship; other types of relationships might still be possible. (We will look at quadratic, cubic, and other more flexible relationships in Section 14).

Example 4.8 (Continuation of Example 3.4.) Suppose we wish to formally test whether the average body mass is the same between male and female penguins. In the SLR model with body mass as the outcome and an indicator of sex as the predictor, this means testing H0:β1=0 against HA:β1≠0. To do this, we can extract the necessary information from the R output:

## # A tibble: 2 × 7

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value conf.low conf.high

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) 3862. 56.8 68.0 1.70e-196 3750. 3974.

## 2 sexmale 683. 80.0 8.54 4.90e- 16 526. 841.Here, ˆβ1=683, t=8.5 and p<0.0001. So we would reject the null hypothesis and can summarize our result as:

We reject the null hypothesis that there is no difference in body mass between female and male penguins (p<0.0001). The estimated difference in average body mass of penguins, comparing males to females, is 683 grams (95% CI: 526, 840), with males having larger average mass.

4.10 Inference for β0

4.10.1 Hypothesis Testing for β0

Hypothesis testing for the intercept β0 works in a similar fashion. For the null and alternative hypotheses

H0:β0=β00 vs. HA:β0≠β00 the t-statistic is: T=ˆβ0−β00^se(ˆβ0)=ˆβ0−β00√ˆσ2(1n+¯x2Sxx) We then compare this value to a Tn−2 distribution. The value of t and its p-value can be computed by hand, or extracted from the standard R output:

## # A tibble: 2 × 5

## term estimate std.error statistic p.value

## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

## 1 (Intercept) -5781. 306. -18.9 5.59e- 55

## 2 flipper_length_mm 49.7 1.52 32.7 4.37e-107In this example, the test statistic for testing H0 is t=−18.9 and its p-value is less than 0.0001, so we reject H0. Of course, this may not be a meaningful test, since it corresponds to the average body mass of a penguin without flippers!

4.11 Exercises

Exercise 4.1 Use R to compute the two-sided p-value for a test statistic t=1.5. Assume this comes from a regression model fit to n=25 observations.

Exercise 4.2 Suppose we fit a simple linear regresion model with celebrity income as the predictor variable and their number of social media followers as the outcome. Explain what the null hypothesis H0:β1=0 would mean in this context.

Exercise 4.3 In the penguin data with flipper length as the predictor variable and body mass as the outcome, what is the conclusion of a hypothesis test of H0:β1=48 against the alternative HA:β1≠48?

Exercise 4.4 In the setting of Example 4.8, what would the null hypothesis H0:β1=600 mean scientifically? Perform a test against the alternative HA:β1≠600 and summarize your conclusions.

Exercise 4.5 Suppose we fit a simple linear regression model with n=100 observations and ˆβ1=10. Given a 95% confidence interval of (5,15), what is the value of ^se(ˆβ1)?

Exercise 4.6 Write a conclusion sentence about β1 for the model fit in Example 3.4.